The surrender-or-else threat of more than half a million British Columbians demanding their government repeal the much-loathed HST has left the B.C. Liberals -- and potentially any party that succeeds them -- with a dilemma they may not be able to solve even if they wanted to.

With the tax already in place and millions of dollars in federal cash connected to the HST already spent, is it possible for B.C. to simply walk away?

The short answer: probably. But it wouldn't be simple, and it sure wouldn't be cheap.

Experts say abandoning the HST before the end of a five-year agreement between B.C. and Ottawa would be a lot more complicated than it was to opt in, raising a series of legal uncertainties while likely leaving the province owing as much as $1.6 billion.

"There's nothing in that agreement that contemplates termination of the HST before 2015 -- it seems to be binding for a five-year term," says Prof. Martha O'Brien, who teaches tax law at the University of Victoria.

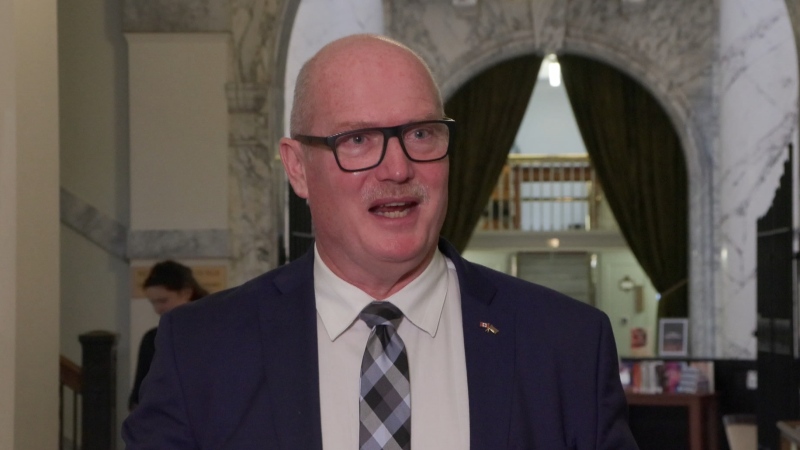

The harmonized tax has proven disastrous for Gordon Campbell's Liberal government, with its sinking popularity, a successful petition opposing the tax, an ongoing court challenge and the prospect of recall campaigns later this year.

Critics including the Opposition NDP and former premier Bill Vander Zalm are demanding the province reverse its decision to adopt the HST, which they complain was announced immediately after an election campaign and has since made a variety of goods and services more expensive.

Their case has been bolstered by a petition that recently collected more than 557,000 valid signatures, enough to force the government to either hold a vote in the legislature or send the issue to a non-binding referendum.

Whatever the choice, Vander Zalm has promised to use the province's unique legislation to mount a recall campaign aimed at unseating government MLAs.

When the HST took effect this past July, it combined the seven per cent provincial sales tax and the five per cent GST. That created a single levy that is administered and collected by the federal government, which then hands a portion of that revenue back to the province.

The fine print detailing exactly how the HST works is contained in a 50-page agreement signed by the province and Ottawa last fall.

What that agreement doesn't explain, says O'Brien, is what would happen if either side backs out before 2015 -- or whether that's even an option.

Adding to the uncertainty is nearly $1.6 billion in so-called "transitional" funding that Ottawa agreed to pay the province to sweeten the deal.

If B.C. tells the federal government it wants out of the HST before that -- either because a new party takes power or the public pressure becomes too much for the Liberals to bear -- O'Brien says it would be up to the federal and provincial governments to sort out the mess between themselves.

"The way I see it is, if the province sent a notice to the minister of finance federally and said we wish to terminate the agreement, you would probably have an intergovernmental negotiation on how to deal with it," says O'Brien.

"They (Ottawa) could say, everything in the agreement looks to a minimum of five years; if (B.C.) is pulling out before that, then they could ask for their $1.59 billion back, from what I can see."

The next B.C. election is in 2013, so if anger at the tax continues, the question of whether and how to back out will remain for whoever wins.

Even though the HST agreement with the federal government reads like a contract, O'Brien says the courts would likely stay out of any resulting dispute, treating it as a policy issue that the politicians would have to solve.

And if the province did leave, depending on how that happens, it might be faced with the complex task of undoing months of HST payments by consumers and low-income tax credits that have already been handed out.

B.C.'s finance minister wasn't available to comment, but officials believe leaving any time before 2015 would mean paying back the entire $1.6 billion, most of which has already been spent or allocated to offset the deficit.

Beyond that, the finance ministry says it hasn't figured out whether the province could cancel the HST because it intends to keep the tax.

A spokesperson for the federal Finance Department simply referred back to the agreement.

Toronto tax lawyer Cyndee Todgham Cherniak, who's been following the HST's recent introduction in B.C. and Ontario, predicts the federal government would take a stern approach if British Columbia ripped up the agreement lest other provinces consider following their example.

"I would speculate they would want the full amount of money back," says Cherniak. "I would think that the federal government would want to send a message that, if you sign onto one of these things, we're going to hold you to it. This isn't just the federal government just writing a cheque."

Cherniak said Ottawa has the ability to compel the province to repay the money, which it could simply subtract from federal transfers to B.C.

Some observers have pointed to Saskatchewan's brief flirtation with the HST two decades ago to suggest B.C. could reverse course if it wanted to.

That province's Progressive Conservative government agreed to harmonize its sales tax in 1991. When Roy Romanow's New Democrats took power in an election later that year, they cancelled the switch before it took effect on Jan. 1, 1992.

But the tax wasn't yet in place and the province didn't have to worry about paying back more than a billion dollars to the federal government.

"There was no federal government interference. We were never challenged legally, we were never challenged politically," recalls Romanow, now a senior fellow in public policy at the University of Saskatchewan.

"I think they (B.C.) have got a whole bunch of new instruments which make it much more difficult for repeal."